Emanuel Pastreich

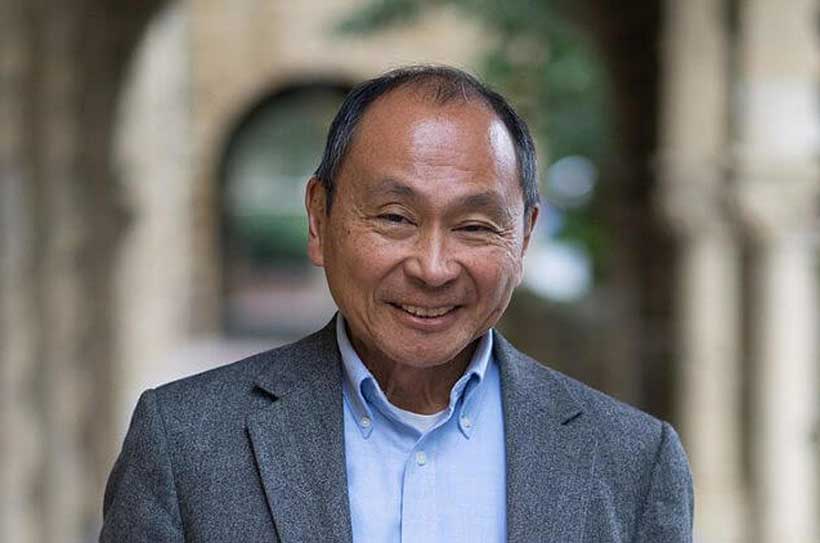

Francis Fukuyama is a leading American political scientist, political economist, and author best known for his booksThe End of History and the Last Man(1992) and theOrigins of the Political Order. He serves as a Senior Fellow at the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law at Stanford University.

We have to start with the simplest of questions. If we want to understand the challenges in East Asia today, we must first consider why it is thatAsia has become so centralin theglobal economy andwhy it plays an increasingly large role inglobal politics. How do you explain the enormous shiftthat we are witnessing today?

Well, there is a significant difference between the economic and the political spheres. Obviously, the biggest shift is to be observed in the economic realm. We can trace it back to the industrialization of China after the Cultural Revolution and rise of the four tigers: South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong. But the shift in terms of political power is a much slower process than the economic shift.

Overall, Asia punches below its weight in terms of its ability to shape the rules for the global system and the direction that global governance is evolving towards. It is an issue of what Joseph Nye refers to as “soft power” – the ability of a nation to project ideas and concepts, build influential institutions and practices. The lag at the level of ideas is even more severe than the lag in terms of political power.

So if we talk about the rise of Asia, we must be sure that we are clear about what aspect of the rise we are referring to. If we ask the specific question, “Why has East Asia’s economic development been so successful?” We can speak with more confidence about a clear rise, although that rise does not necessarily fulfill all the traditional expectation for growing power and influence. We can be sure; however, that China will continue to increase its influence in global affairs for the foreseeable future.

And yet China’s rise is profoundly paradoxical. China is increasing influence in the political and economic spheres today, and is engaged in large-scale aid projects that are unprecedented in its history. At the same time, if you go to Shanghai, you will find more and more Chinese students studying English and trying to go abroad to study at American universities. There is more interest, not less, in moving to advanced countries now than was the case twenty years ago.

The trend is real, but it perhaps has more to do with the fact that there are simply more Chinese who have the money to send their children to the United States for their studies than anything else. Nevertheless, we can see that although China has the economic, the cultural and educational soft power is still lacking.

For all its weaknesses, the United States projects a tremendous amount of soft power globally. China cannot match that power yet.

But what is it exactly that gives the U.S. that advantage? Why has it been so hard for China, Korea and Japan, in spite of astounding economic growth, to have that sort of cultural impact? Certainly the cultures are extremely sophisticated and the level of education is very high.

We are seeing some changes these days, but the building of institutions, the growth of global networks, and the acceptance of new cultures takes generations.

Korea has done well in terms of culture. If you look at the spread of K-pop, Korean soap operas and Korean movies, Korea is producing a highly competitive culture that is expanding rapidly, even including spheres like manga and anime that were once exclusively Japanese. But such cultural influence has very little to do with GDP.

Significant shifts may come, but they will not be fast.

I suppose that the dominance of the English language is also an important factor.

The power of English has a long history, dating back to the British Empire, but its continued dominance is in part a reflection of culture, and in part a reflection of U.S. dominance in international business. In spite of the remaining dominance of English, we can perceive significant shifts. People are starting to learn Mandarin around the world, and that trend will continue. For some in Africa, Chinese seems like a very significant language. Eventually cultural influence will follow from growing economic power, but the lag time is significant.

And we are in an age of unprecedented age of globalization that defies previous precedents. For example, if you read the published statistics concerning members of the Chinese Central Communist Party committee, you will see that an extraordinary number of them have either a relative living abroad or own property abroad. They are committed to a global economy and they have an interest in the economy of the United States. We can see those overseas investments as a way to stash the cash, but there is also a sense in which those overseas investments are a security net of sorts. I do think there’s a sense that Western countries, whatever problems they may have, are fundamentally more stable politically than developing nations.

Therefore, despite all of China’s remarkable success, continued stability and prosperity is not something that they can take for granted? The accumulation of capital is not a replacement for quality of life, for getting a quality education, having safe food to eat. Even the superrich in Beijing can have kids with asthma who become terribly sick because of air pollution.

The author Lee Chang Rae recently published a novel entitled On Such a Full Seadescribing an authoritarian state in a megacity B-Mor (the former Baltimore) which is populated with immigrants from a village in “New China” that become uninhabitable because of climate change. The novel suggests that we may encounter a world quite different than our common “rise and fall of great powers” assumptions and that technology and climate change will be major factors. The entire world is being impacted by China’s rise and Lee Chang Rae’s scenario is not far-fetched.

There is a debate in the West, and to some degree in China, as to whether China is really capable of fundamental innovation. I probably fall into the camp of those who say that you we should not underestimate China’s ability to make profound shifts. China has changed far more than anyone imagined since the Cultural Revolution and it has a long history of institutional transformation. Although much of China’s recent economic and intellectual progress has been a form of catch-up. China is a vast country with many smart people. I would not assume that just because China lacks great political freedom that this means China isn’t going to be able achieve astounding progress, to innovate in technology and institution building.

Certainly China has a long tradition of good government and of institutional innovation. From the Tang and Song Dynasties to the Ming and Qing Dynasties, China has been able to generate internal reform on many occasions. There have been some scholars like Daniel Bell at Tsinghua University, in his bookThe China Model: Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy, or Zhang Weiwei of Fudan University in his bookThe China Wave: Rise of a Civilizational State, who argue that China is fundamentally different than other nations in that it is a civilization, not a nation state. Is there perhaps something transformative of China that seeks to remake the entire world, not just expand into new markets?

I’m a little skeptical of such efforts to see some sort of new Confucian vision in the chaos that is the present Chinese political economy. I just do not see an integrated package; it’s an incoherent package. The official message coming out of China in its official sources is still taking Marxism-Leninism as its base. Perhaps there is a sincerely interest in the past, but basically Chinese are pretty confused about Confucianism. Although it may feel good to think on is building on a great tradition of millennia. But when push comes to shove they are back to Marxism or neo-liberalism. They end up filling the ideological vacuum with consumerism and greed. As long as the economic growth keeps up, they will be alright. But I do not see too much Confucian civilization in the hard choices that Chinese politicians make.

But in the West things are at last shifting a bit. Western intellectual are taking a stronger interest in Asia and reading and writing about China and its culture and politics. How broad is the interest in East Asia in Washington D.C.?

Although interest in Asia has risen remarkably, it is probably still far from what it should be. The rise of China has triggered broad introspection about Western and American institutions and their shortcomings. There have been some debates in the fringes, but the serious reorientation has not started. Most people in the West acknowledge there is a new drive in China and they express concern about job losses in the United States. But there are few who look at the rise of China and East Asia as a challenge to the dominance of Western civilization.

What do you think is the primary challenge to the U.S. and Europe today?

Many social scientists in the United States have postulated that economic freedom without a corresponding degree of political freedom is not sustainable. They assume that China will have to open up its political system and to democratize in one way or another. But there are serious problems with this assumption. If we think long term, say thirty years in the future, could we have a China in which economic growth is significantly higher than that in the West, a Chinese economy that has completely displaced the U.S. in scale and impact, but still have a China in which the government calls the shots domestically and internationally? Such a scenario is entirely possible and could create immense challenges to current global institutions. Few in the West want to imagine such an outcome. But that is not an excuse for presenting wishful thinking as critical analysis.

At the same time, the question of freedom is a complex one. Certain areas of Shanghai, for example, have access to Face book and Google and there are virtually no cases of interference from the government – if you are part of the “international community.” Many American expats feel oddly freer in that Chinese environment.

Yes, there are clearly pockets in China that are quite open these days. Globalization produces all sorts of complexities.

And what about Europe? How has the rise of Asia impacted France, Germany, Italy and other European powers?

What is striking about Europe is just how little attention they pay to China. Although I wish the United States took Asia seriously, compared with Europe, we are doing a pretty good job. You would be amazed to see how much Europeans still are talking about the challenge from America and the American model for business. They are having trouble getting their heads around the fact that China going to be a major player in the world and that what happens in the Chinese economy impacts the European economy. Similarly, the study of China, Japan and Korea in Europe is far behind the United States. There are not that many Chinese speakers and almost no one who can deliver a speech or read a book in an Asian language.

We have stressed China so far in our conversation, but in reality Korea and Japan remain quite significant. Might there be a risk that America focuses too much on the China challenge and loses track of the important developments in the rest of Asia. After all, Korea and Japan are major players in Southeast Asia and Africa, often displaying a greater sophistication than China.

Asia is polycentric, multi-polar, and constantly evolving. There is no uniformity in Asia in terms of geopolitics and culture and each of those countries is a separate world to itself, even as it overlaps in trade and commerce with its neighbors and with the United States. It is a challenge for Americans to keep up with that region.

The conditions are really different in each country. If we take a slightly longer-term horizon, all of Asia will be caught in this demographic trap (declining and aging population) which may have unintended consequences. Japan was the first to experience that shift, and we have seen articles about aging villages in the Western media for some time. But the trend for the future is actually more severe in Taiwan, South Korea and Singapore. These countries are struggling to come up with some solution to the aging population crisis, and the resulting growth of a multi-cultural society.

But if you looked at middle-class and upper-middle class Caucasians in Europe or the United States, is not that population is more or less following the same trajectory as the aging populations of Korea or Japan.

One cannot make sweeping statements. The fertility rates for Caucasians in the United States remain higher than that of countries like Korea and Japan. In the case of Scandinavia fertility rates have risen above the replacement rate. I speculate that countries that have the lowest fertility rates in the world are those in which you have a high level of female education, but still socially conservative mores that limit career opportunities for women. That is exactly what we find in Japan, Korea, Taiwan and Singapore, where a lot of women don’t want to enter into marriages that require them to stay home and raise families, but the childcare facilities necessary for them to pursue careers do not exist. In Japan, the average age for the marriage of women keeps rising every year.

It’s amazing that although many families in Korea or Japan place so much emphasis on education for both boys and girls, there is an absolute distinction after graduation from college. Equality of opportunity suddenly ends when the student receives a diploma.

I met a professor at Julliard who was just livid because although many of his best piano students are Korean women, not a single one of them has turned that talent into a career as a musician. Despite all their talents, they dutifully go back to Korea and marry a rich corporate executive. Their outstanding musical talent becomes, he lamented, but an adornment, a hobby. There was no opportunity for those women to pursue a career in music.

Let’s talk about the current tensions in Asia, specifically those between China, Japan, and Korea. Although some make grim analogies between Asia today and Europe just before World War I, it seems to me that the conflicts over islands are fundamentally different in its nature from the battle over territory occupied by large populations.

I think the conflicts are quite serious because they are powered by the rise of nationalism in Korea, Japan, and China. Young people in each of these countries are growing more nationalistic than was their parents’ generation, and that trend is quite dangerous. Honestly, I am quite worried by what I see happening today. The territorial disputes are not inherently critical, but they take on tremendous symbolic significance and they are at the center of a struggle over geopolitical power. The fight over the future of the Senkaku Islands is not just about a few uninhabited rocks. It is a contest over who will set the rules in Asia, China or Japan. It is this larger question that absorbs the interests of both countries.

It’s still a different situation from, say, Alsace-Lorraine; no one lives there after all.

Sure, no one wants to start a war over a stupid bunch of rocks. But history shows that strange things like that can happen.

What are your thoughts about the U.S. and its position in East Asia? What do you think is the appropriate role for the U.S. to play in Asia going forward?

I think the U.S. needs to adjust to growing Chinese power but needs to be mindful of existing commitments. The accommodation of Chinese power cannot come at the expense of traditional allies – Japan, Korea, etc. Doing that is going to be very difficult. In the case of Japan, the Japanese have actually provoked a lot of the problems that they’re in right now, by the kind of nationalistic planes of revisionism that is going on there.

I am concerned by nationalist activities throughout East Asia. But as someone who taught Japanese studies for many years, I am disturbed especially by the purging of information about the Second World War from school history books and the shutting down of museums that provide an accurate narrative of what Japan did during the war. Japan is a sophisticated nation with a highly educated population. Such steps are just wrong.

There are definitely a lot of disturbing trends in Japan. The majority of the Japanese people do not support these actions, but there is a significant nationalistic right that has not accepted the outcome of the Second World War in the way that the Germans have.

You have grown up in the United States, but your family is from Japan. Does that impact your perspective?

My perspective on East Asia is completely American. I have no sympathy for the Japanese nationalists. The United States has an alliance commitment to Japan, but the position Japan has taken on many disputes with its neighbors has been self-defeating.

Coming back the U.S. role in East Asia, you suggest that the United States must engage China, and recognize its new status, but that there may also be some legitimate reasons for the United States to remain wary of China’s intentions. What specifically must the United States do to create stable security architecture in East Asia?

I feel that the U.S. needs to promote multilateralism in Asia and to consider multilateralism to be in its own long-term interests. The United States has certain advantages in its bilateral alliances. But the use of bilateral relations in Asia can also undermine American influence.

For example, China would like to deal with all ASEAN countries individually, through bilateral exchanges. But can we solve the complex multilateral disputes over coral reefs in the Pacific by a series of bilateral discussions? I think we need to do so through ASEAN, other international bodies, or new institutions that we will build.

I made a proposal inForeign Affairs about a decade ago for a multilateral structure related to diplomacy and security in which all countries, including China, can talk openly about defense budgets, confidence-building measures, and other topics and come to meaningful resolutions.

I have noticed thatKoreans, whether politically conservative or liberal, are committed to a multilateral vision of the future. Unlike the United States or Japan, there is no conservative faction that wants to dismantle multilateralism and pursue national military power without regard for international opinion. Perhaps this is a result of Korea’s position in multiple trade agreements that make its economy inherently multilateral.

I have noticed a strong interest in multilateral institutions in Korea. Such arrangements serve as a force-multiplier.

Let me close with a question about technology. How do you think evolving technologies (drones, cyberspace and other technologies with dual uses) are changing the nature of conflict and international relations, and what are the implications of those changes for East Asia?

I think you can see profound changes already in cyberspace. Already there are essentially no rules whatsoever. For example, if you hack into another country’s computer system, whether the computer belongs to a corporation or to the military, does that constitute an act of war? Who counts as a representative of the government of a country in cyberspace?

We have no agreement about the remedy to growing cybercrime. In fact we do not even agree on what kinds of responses are acceptable. Even if you do know who committed the crime, experts do not agree on how serious it is. And numerous reports of hacking have tended to make the public somewhat skeptical.

I suspect that rules and regulations about online crimes are going to be harder to enforce simply because the technology is so rapidly changing and often it is hard to show there has even been a crime.

Emanuel Pastreich is Director of the Asia Institute. Theoriginal versionof this article is available at Asia Today. This is the first of an interview series organized by theAsia Institute.

Courtesy: The Diplomat